Tuesday Morning — Notebook servers and Conda Environments

Credits for today’s sessions: material from previous tutorials by Andrea Telatin, CLIMB BIG DATA documentation, fresh material from Mark Pallen, Powerpoint presentation from Phil Ashton, ChatGPT used to proofread, to expand on some points and create images.

Please feel free to use the Google Docs to ask questions

Handling files and commands within a Jupyter Notebook Server

Although your MacBooks run a version of Unix, most bioinformaticians prefer to use Linux and so most programs and pipelines work best on Linux. In bioinformatics, most researchers also prefer to use remote virtual servers over their own personal (bare metal) machines for several important reasons:

- Bioinformatics analyses, such as genome assembly, sequence alignment, or large-scale data mining, can require substantial computational resources (e.g., CPU power, memory, and storage).

- Personal computers, particularly laptops, often do not have the processing power or memory to handle these large datasets effectively.

- By contrast, remote servers provide access to high-performance computing resources, which are specifically optimized for demanding tasks, ensuring faster and more efficient data processing. Here we are using a cloud platform, CLIMB-BIG-DATA, offering dynamic scalable resources.

- Virtualization allows multiple users to share the same physical hardware while operating in isolated environments, making it a more cost-effective solution.

- Virtual servers can be easily scaled up or down based on demand, meaning researchers only pay for the computing power they use, which is especially beneficial when dealing with fluctuating project needs. Virtual servers also offer enhanced redundancy and fault tolerance, meaning that if hardware fails, another server can quickly take over without data loss or significant downtime. This reliability is crucial for long-running bioinformatics computations, which could otherwise be disrupted by hardware failures.

We will be using a Jupyter notebook server, which is an easy-to-access web-based platform that allows users to create and interact with Jupyter Notebooks, which in turn are documents that can contain live code, equations, visualizations, and text. The server runs the computational backend that provides command line access to a Linux shell, but can also processes code cells written in languages like Python, R, or Julia, and returns the output to the browser interface where users can view and manipulate results.

Before we get stuck in to using a Notebook server, let’s set the scene with a short Powerpoint presentation.

How to launch and access a CLIMB BIG DATA notebook server

- You have been sent an email invitation that explains how to access the CLIMB-BIG_DATA account interface Bryn https://bryn.climb.ac.uk/ and set up an account.

- Read this information about authentication:

- Using the navigation menu on the left hand side, select ‘Notebook servers’ under the ‘Compute’ subheading

- Click the ‘Launch notebook server’ green action button on the right hand side

- Select a ‘Standard server’

- Click ‘Launch Server’ and monitor the progress bar

- Once ready, click the url beneath the ‘User notebook server’

- On first login, you may be asked to authorize access to your Bryn account. Click ‘Authorize’

- The JupyterLab interactive computing interface should open in a new tab.

Finding your way around the JupyterLab interface

Let’s now spend a few minutes exploring the JupyterLab interface using the documentation provided by JupyterLab to get started. Open the link in a fresh browser window and then return here when you have worked through the documentation there. Don’t worry about covering all the details there. Just work out how we can use the Notebook terminal together with the added benefits of having a graphical user interface to work with files. Don’t worry

Fundamentally, your screen is divided into a few areas. You’ll see context menus at the top (File, Edit, View, Run etc.), a file browser pane on the left, and an activity area that initially displays a launcher interface with tiles. Clicking on one of these tiles will open a new tab in the activity area.

The Terminal

The terminal allows us to access a system shell (just like on ypur MacBooks), so let’s start there.

Select File -> New -> Terminal, or click the Terminal icon on the launcher pane. You’ll get a new terminal tab in the activity bar, and find yourself in a bash shell.

Who is jovyan?

Looking at your bash prompt, you’ll notice that your username is jovyan (derived from “Jupyter”). Why does everyone have the same username in this environment? That’s because your notebook server is running inside a container. Containers are lightweight, self-contained environments that bundle an application (in this case, the Jupyter notebook server) together with its dependencies, ensuring that it runs consistently across different systems.

The container instance is private and linked to your specific user storage on the system, but the actual image (which includes the software, configurations, and libraries) is the same for everyone using the platform. This is why it’s unnecessary to have unique system users for each individual—everyone operates within the same standardized environment, hence the shared username.

What is a container?

A container is a technology that allows you to package up an application, along with all of its dependencies, libraries, and configurations, into a single isolated environment. This guarantees that the application runs consistently, no matter where it’s deployed. Unlike virtual machines, which simulate an entire operating system, containers are more lightweight because they share the host system’s kernel, making them faster and less resource-intensive.

In a Jupyter Notebook server context, containers allow multiple users to have their own private instances, even though they all use the same underlying software image. This ensures consistency across users, simplifies deployment, and provides isolation—what happens in your container doesn’t affect others. It’s a key technology in environments where reproducibility and ease of scaling are important, like in data science and bioinformatics workflows.

TLDR: Don’t worry about it! Inside your notebook server, everyone’s username is set to jovyan because you’re working inside a standardized container environment that provides all the necessary tools and libraries for your Jupyter notebooks.

Where am I? Who am I?

By default, you’re in a bash shell running against the base operating system of the climb-jupyterhub container image (which is based on a flavour of Linux called Ubuntu). You’ll see in your bash prompt that you’re in your home directory (represented by the tilde character ~).

jovyan:~$ pwd

/home/jovyan

Using the Notebook terminal

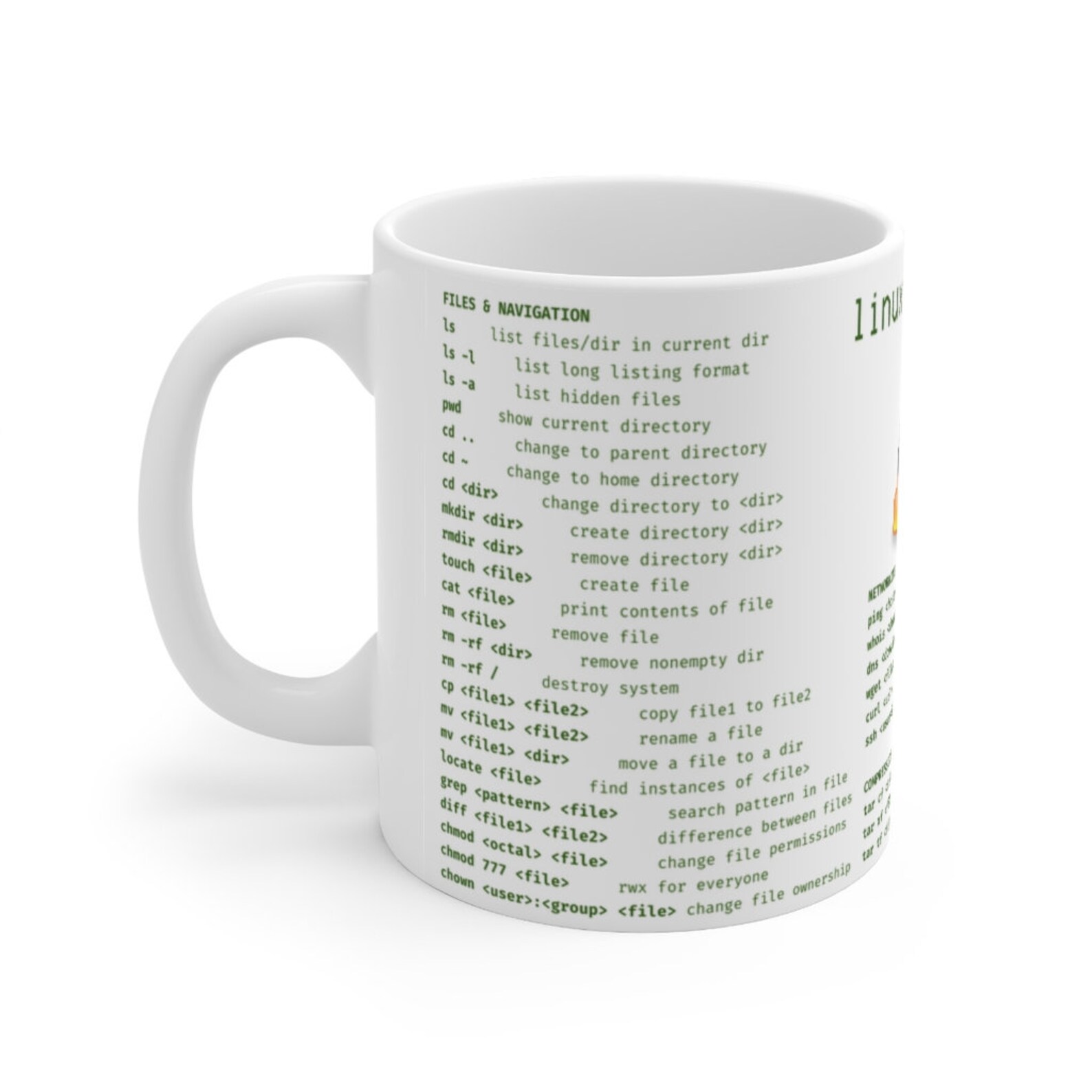

Within the Terminal here, you can do almost all the things we did yesterday using Unix on your MacBooks.

Let’s just have a play and re-do some of them.

touch testfile.txt

curl -o voyage_of_the_beagle.txt https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/944/pg944.txt

cat voyage_of_the_beagle.txt

head voyage_of_the_beagle.txt

tail voyage_of_the_beagle.txt

wc voyage_of_the_beagle.txt

grep naked voyage_of_the_beagle.txt

ls -l

rm testfile.txt

ls -l

Note how files appear and disappear in the column to left. You can also view and search and edit the files with that interface!

Feel free to try out whatever other commands interest you!

There is no sudo here

One Unix command that you cannot use on this Notebook server is sudo. Try it

sudo touch file.txt

jovyan doesn’t have sudo privileges. This may seem restrictive, but we’ve pre-configured the climb-jupyter base image with everything you’d likely need sudo for pre-installed. Everything else should be installable via package managers, such as Conda, which we are going to learn more about after coffee.

Coffee break

Conda

We will now cover the importance of using a package manager called Conda for installing software and managing environments, especially when working in Jupyter Notebooks on complex bioinformatics projects.

Let’s start with a Powerpoint presentation.

What is Conda?

Conda is an open-source package management and environment management system. It allows you to easily install, update, and manage software packages, as well as create isolated environments for different projects. Conda supports multiple programming languages, such as Python, R, Ruby, and others, making it a versatile tool for various domains.

- https://docs.conda.io/projects/conda/en/latest/user-guide/getting-started.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conda_(package_manager)

Why is Conda Useful?

Conda is especially useful in the following scenarios:

-

Package Management: Conda simplifies the installation of software packages, whether they are bioinformatics programs or various libraries they need to run.

-

Environment Isolation: Conda helps you create isolated environments where you can install different versions of the same software without conflicts. This is crucial in projects that require different libraries or dependencies that may not work well together.

-

Cross-Platform Compatibility: Conda works across various operating systems, including Linux and Windows. This ensures consistency when working on collaborative projects with team members on different systems or when deploying solutions on servers.

-

Jupyter Notebooks: When working in a Jupyter Notebook environment, Conda allows you to create and switch between environments effortlessly. This is helpful when running notebooks that require different software packages or specific versions of libraries without causing issues across the system.

Setting Up Conda Environments

Conda simplifies installing packages, but a common issue arises with conflicting versions:

- You may want to use the latest version of

your_favourite_programwhen using it on its own, which might say beyour_favourite_programv3.13, but if you are running a pipeline that might require an older version, sayyour_favourite_programv2.4and if the pipeline just tries to call on the latest version that uyou have installed, it will fail to progress. - A typical bioinformatics workflow involves dozens of different tools, each requiring specific libraries and dependencies.

- Installing everything in what is called an environment can result in conflicts between versions of the same tool.

To solve this, Conda allows you to create isolated environments, where each environment is an isolated, self-contained workspace with its own set of packages, libraries, and configurations, independent of other environments. Each environment operates independently, meaning you can have multiple environments with different versions of the same software, avoiding conflicts between dependencies. This ensures that tools in one environment don’t conflict with those in another.

Creating and Managing Conda Environments

Conda makes it easy to manage software and environments, helping you keep your projects organized and free from conflicts. You can use Conda on any Unix machine, but one important caveat applies when using it here on the CLIMB-BIG-DATA Notebook servers. In Conda, the base environment refers to the default environment that is created when Conda is first installed. It is the environment that contains the core system packages and dependencies needed for Conda to function, as well as a minimal set of commonly used packages (like Python). But on CLIMB-BIG-DATA Notebook servers, you cannot install new software to the base Conda environment. Let’s have a look at why.

conda info --envs

base /opt/conda

The base Conda environment is installed at /opt/conda. Since we are running inside a container, any changes made to this part of the filesystem will not be retained once the container is stopped and restarted (unlike your home dir and shares, which are persisted).

We’ve made the base environment read only to prevent any confusion.

Tip: You must create a new Conda environment before installing software!

Creating new conda environments

Let’s see how we can create new conda environments.

Let’s start with an environment called bioinfo_fun.

conda create -n bioinfo_fun

conda activate bioinfo_fun

If you try listing channels, you’ll see you already have conda-forge and bioconda set.

conda config --show channels

Installing Programs in Conda Environments

Bioconda is a distribution of bioinformatics software for the Conda package manager. Conda is an open-source package manager that can install software and manage environments. While Conda is general-purpose and can manage software written in any language, Bioconda specifically targets the bioinformatics community, with a collection of over 7,000 bioinformatics packages, making it one of the largest and most comprehensive software distributions available for computational biology.

A straightforward bioconda tool that can calculate the GC percentage for sequences is seqkit, which provides a variety of functionalities for sequence file manipulations. Among its many utilities, it has a subcommand to compute the GC content.

To check if the program seqkit is available in bioconda, and which versions:

conda search -c bioconda seqkit

To install a package, we simply replace search with install. If we also add -y we will not be prompted with messages and conda will try to install directly.

conda install -y -c bioconda seqkit

A few words on FASTA files The FASTA format is a simple text file format, and it’s as widely used as it is old (1985). Each sequence has a name, extra information (comments) and the sequence itself, and one or more sequences can be stored in the same file, one after the other. The sequence itself can span multiple lines.

Here an example:

>P01013 GENE X PROTEIN (OVALBUMIN-RELATED)

QIKDLLVSSSTDLDTTLVLVNAIYFKGMWKTAFNAEDTREMPFHVTKQESKPVQMMCMNNSFNVATLPAE

KMKILELPFASGDLSMLVLLPDEVSDLERIEKTINFEKLTEWTNPNTMEKRRVKVYLPQMKIEEKYNLTS

VLMALGMTDLFIPSANLTGISSAESLKISQAVHGAFMELSEDGIEMAGSTGVIEDIKHSPESEQFRADHP

FLFLIKHNPTNTIVYFGRYWSP

The header line must start with a “>” character. The sequence identifier, or sequence name, it’s P01013 (the first word before a white space) The sequence comment, in this example, is “GENE X PROTEIN (OVALBUMIN-RELATED)” The sequence itself is a protein sequence, commonly stored in uppercase (but for DNA it’s commont to find lowercase sequences too).

Demonstrate GC Percentage Calculation Let’s check that seqkit has been installed.

conda seqkit -h

This should bring up help information for the program.

Now let’s do a toy exercise to see it working.

First, let’s create a sample FASTA file:

echo ">sample_sequence" > sample.fasta

echo "AGCTAGCTAGCTAGCTA" >> sample.fasta

- Note that using

>>means the text is added to the end of the existing file. If we typed>the current file would be overwritten.

Check what the file looks like

cat sample.fasta

Now, compute the GC content:

seqkit fx2tab sample.fasta --gc

This command will give you the GC content of the sequence in sample.fasta.

Command Breakdown:

Here’s a detailed breakdown of the command:

-

seqkit: This is the main tool you’re calling. SeqKit is a command-line program for manipulating and analyzing FASTA/Q files. It has many subcommands for tasks like searching, filtering, and converting sequences. -

fx2tab: This is one of SeqKit’s subcommands. It converts sequences in FASTA/Q format into tabular (tab-delimited) format. This is useful for making sequence data easier to handle, analyze, or integrate into pipelines that work with tabular data.In the tabular format:

- Each sequence will appear as a single row.

- Default columns typically include information like sequence ID and sequence data.

-

sample.fasta: This is the input file. It is the name of the FASTA file that contains the DNA or protein sequences. FASTA is a text-based format for representing nucleotide sequences or peptide sequences, with one header line (starting with>), followed by the sequence data. -

--gc: This flag instructs SeqKit to calculate and include the GC content in the output. GC content is the percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases in a given DNA sequence, which is often used as a metric in genomics and bioinformatics to assess sequence composition.

What This Command Does

This command reads the sample.fasta file, extracts each sequence, and outputs it in a tabular format. Along with the sequence ID and sequence data, the GC content for each sequence will also be calculated and included as a separate column in the output.

NB: seqkit is versatile and offers many other sequence-related utilities, so it’s not just limited to computing the GC content.

We will play with it again after lunch.

Time for lunch!